With the expected growth in the number of fully electric cars and plug-in hybrids in coming years, analysts predict that the demand for aluminium will increase tenfold by 2030. But how will the more extensive use of aluminium impact the car recycling industry?

Tekst Jens Holierhoek

According to British CRU, a leading research agency specialising in metals, sales of plug-in hybrids and fully electric cars will comprise no less than 30 per cent of total global sales by the year 2030. At present, only 4 in 100 cars sold are electric. With the increase in plug-in vehicles, the use of aluminium will increase tenfold by the year 2030, predicts CRU. The reason is because aluminium is the perfect metal for use in electric cars. After all, the heavy battery pack is compensated by the lightweight aluminium. Research conducted by the International Council of Metals & Mining (ICMM) shows that if you replace the steel parts of a car with aluminium, you cut the total weight of the car in half. The assumption is that each weight reduction of ten per cent leads to a reduction in the energy consumption from six to eight per cent. A car made of aluminium is 30 to 40 per cent more efficient than a comparable steel model.

Steel fights back

Whether CRU’s predictions will come to pass is still not certain, since steel has recently experienced renewed interest. As a result of technological progress, electric cars have an increasingly larger action radius, thwarting the call for a lightweight and often more costly construction method in the future. Moreover, the addition of new electric car options increases competition. Car manufacturers hope to win over consumers by offering less expensive steel models. In addition, steel continues to undergo development. The use of the latest types of steel is expected to make cars 25 per cent lighter in weight.

Plug-in hybrids

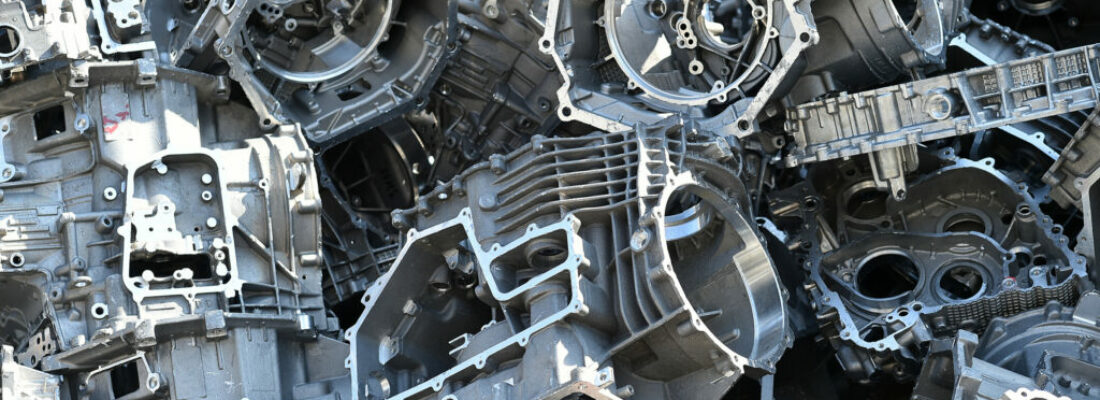

The extent to which the use of aluminium will increase can be disputed, but both friend and foe agree that it will be a significant one, even if only due to the combined use of aluminium and steel. Brands like Nissan and Volkswagen have already made the switch to steel as the main component of their electric Leaf and e-Golf, but both models still contain 171 and 129 kilos of aluminium respectively. The car industry also expects a boost in sales of plug-in hybrid models. These are partly electric – usually for up to 50 kilometres – but still have the familiar fuel engine under the hood. The car industry uses aluminium for the combustion engine, transmission, and battery casing, thereby increasing the demand for the metal. According to the CRU, plug-in hybrids (as with fully electric cars) use 25 to 27 per cent more aluminium than the average car with a fuel engine.

The good news for the automotive industry is that aluminium is anything but scarce. At eight per cent, it is the second most abundant element in the earth’s crust. Then there’s the downside: the production of aluminium car parts is more costly than steel. Around four kilos of bauxite and fifteen kilowatt hours of energy are needed to produce one kilo of aluminium. The bauxite is used to melt the aluminium until it transforms into a mineral called cryolite. Electrolysis, which entails conducting an electric current through it, separates the oxygen atoms from the aluminium, so that the aluminium can be processed further.

Recycling aluminium

Although the production of aluminium is an energy guzzling and expensive one, the recycling of aluminium is anything but. The material is 100 per cent recyclable and can be used repeatedly – almost infinitely – claims the industry with pride. Around 75 per cent of all aluminium ever produced is still in use, says The Aluminum Association and, in the automobile industry, the recycling percentage is even higher than 95 per cent. The recycling of aluminium requires around five per cent of the energy used for its primary production.

Thanks to all the impressive facts and figures, aluminium is the ideal recycling material. But a bit of nuance is needed, emphasises Dr. Antoinette van Schaik, owner of the consultancy firm Material Recycling and Sustainability (MARAS) B.V. and a graduate of the TU Delft with a PhD in car recycling. “The footprint for aluminium recycling is far better than primary use. But aluminium is only recyclable if you organise the recycling process right and give considerable thought to how you plan to use the aluminium in the design. In other words, how and in what form will the aluminium be used? As a metal or aluminium oxide in, for example, a condenser or as a filler in plastics?” After all, aluminium is highly reactive and extremely susceptible to contamination. If you combine aluminium with other materials in a car – as is commonly done – you run the risk of contamination. That contamination makes the recycling process more difficult and, in some cases, impossible, says Van Schaik. “In the shredder and sorting process, aluminium cannot always be completely separated from the other materials with which it may be combined in more complex parts. Part of the contamination in the aluminium recyclate can become trapped in the slag used in recycling. That salt slag functions as a sort of waste flow. But materials more precious than aluminium, such as copper or steel, remain in the aluminium mix and lower the quality and usage possibilities”. It is not possible to remove it and requires too much energy.

With the enormous increase in plug-in vehicles, the use of aluminium will increase tenfold by the year 2030

In practice, primary aluminium or clean scrap directly from aluminium production is often added to the recycled aluminium. This ‘dilution’ is necessary to obtain the right quality of aluminium alloy. This is not an ideal situation from a cost and environmental perspective.

Challenges

The reactive nature of aluminium is also clear in the ‘sandwich panels’ used extensively in the car industry. In this case, they adhere plastic or composite materials to aluminium. The layer of aluminium oxide on the surface of the plates is lost in the process. Moreover, the aluminium on the plate reacts with the carbon in the plastics and adhesives, which can lead to the formation of aluminium carbide (and other non-recyclable combinations). In that process, methane can form, which is a powerful greenhouse gas. A ton of methane has the same greenhouse effect as 25 tons of CO2.

If you are able to purify the metal when recycling aluminium, you need to consider the type of alloy in order to reuse it as effectively as possible, says Antoinette van Schaik. Is it a wrought alloy that is hardly alloyed and, consequently, highly pure or an ‘everyday’ casting alloy to which all kinds of other metals have been added? It goes without saying that you don’t want to combine the high-quality variant with an alloy containing an average composition. This is once again proof that aluminium recycling is challenging. Or, as Van Schaik rightfully puts it, “You can’t put just one recycling label on aluminium. The part of the car where the aluminium originates and the form in which it was used are extremely relevant.”

From shredder to dismantler

If the predicted use of aluminium in the car industry increases significantly, in view of the complexity of recycling in relation to the design, growing pressure will also be placed on the recycling of the metal. The current standard processing route in the automotive recycling industry is selective dismantling/depollution, followed by shredding and separation, although dismantling is increasingly preferred. Van Schaik adds, “Electric cars are built differently and because of the batteries and electronics, for instance, have to be dismantled in parts.” For the reuse of aluminium, the best option would be for car manufacturers to build their EVs in a modular manner and to orient the recycling process more towards modular dismantling, she believes. In doing so, the reclamation possibilities and limitations of the metal recycling processes need to be considered. This makes it possible to separate and process the metal in as many ‘bite-sized’ pieces as possible with the optimal composition (within the requirements of product functionality). She argues in favour of manufacturers integrating the recyclability of their cars into the design in as much detail as possible.

Van Schaik: “You can’t put just one recycling label on aluminium. The part of the car where the aluminium originates and the form in which it was used are extremely relevant”

Closed-loop

A number of car manufacturers have already started focussing on aluminium recycling, such as Jaguar Land Rover. At present, around half of the aluminium used by this British company in its cars is recycled, thanks to a closed-loop system that it established together with the recycler, Novelis. Next year, Jaguar Land Rover wants to launch a second project to boost the percentage of recycled materials used in its cars to 75 per cent.

Novelis has also established a closed-loop system for the American car manufacturer, Ford. As with Jaguar Land Rover, aluminium production waste is collected and remelted by Novelis into raw materials for new aluminium models. But the closed-loop system at Ford takes this a step further because the aluminium parts from end-of-life Ford models are also recycled. The parts containing aluminium are dismantled, after which they progress via a shredder and de-coating process to the Novelis remelter. A new, large block of aluminium is the result. Ford recycles and reuses around 90 per cent of the aluminium it uses, giving it the largest closed-loop recycling system, according to Novelis. Novelis’ aluminium already makes its way into around 225 different car models. This number is expected to grow quickly.